By Ho See Wah

‘Departure’ seems like a melancholy word. There is a register of saying goodbye and of leaving behind, a loss to be had. Yet in the same instance, ‘departure’ may connote an anticipation, one of starting new journeys and a tentative excitement for what lies ahead. Then perhaps, we can read such happenings as a transitory event, a movement from a certain place to another in the same way that bodies pass through train stations and airport terminals—a realm of possibilities nestled within this practical application. In this case, it may be useful to think of it as an active doing and a vibrant becoming into something new.

With this framework in mind, we can begin to delve into the works of Yanyun Chen, Hong Zhu An and Prabhavathi Meppayil, which are put into proximity with one another for the exhibition Departures (April–June 2024) at STPI Gallery. These three artists had undertaken their residencies at STPI’s Creative Workshop between 2019 to 2022, where they had embarked on a unique journey of translating their usual practice into the mediums of print and paper in collaboration with the Creative Workshop team. This is often a good challenge and paves the way for stimulating experimentations, as it enables a departure from the invited artists’ studio processes towards another climate for art-making.

Yanyun Chen

Chen at work in STPI’s Creative Workshop, 14 December 2021

Chen at work in STPI’s Creative Workshop, 14 December 2021

The works here by Chen take on an ephemeral-like quality, in obvious contrast to her usually-dense charcoal drawings which she is highly-skilled in and well-recognised for. In the span of a short and wild three weeks,¹ the artist was impelled to experiment beyond the familiar due to working with foreign methods and collaborators. Chen, therefore, aimed to push each piece further and further in a generative process, with each being a departure from her previous practice, the previous test prints, and even the previous copy within the same series of work. Of significance is the use of the watermarking technique, performed on handmade mulberry paper in STPI’s paper mill. It was the first time where the artist had worked closely with and within the substrate itself, rather than just as a surface to coat charcoal on.²

Yanyun Chen, Seen, screen, scatter, 2021, Mulberry charcoal and bark on STPI handmade paper with watermarks, 180 x 55 cm (left); 180 x 55 cm (right)

When we think of watermarking in today’s time, an administrative sentiment may come to mind, one that we associate with the digital sphere to denote a copyright, an intentional data disruption to the original file; it all exists within the glassy-smooth and flat surfaces of our devices, out-of-reach. However, watermarking returns to its physical form here, a practice that is often overlooked or forgotten as we dive more and more into the digital stratosphere. In fact, the original method of producing a watermark is a highly material act where hands meet pulp, where fibres make their mark, where an image is created as part of the paper itself by strategically varying the thickness of its depth during the wet phase of papermaking. For Chen, this was a decidedly ‘opposite’ process from her charcoal drawings, where the watermarking/drawing ‘peers into’ the inner world of the material itself, a hidden domain that we are barred access to, in comparison to ‘bringing out’ a subject from the paper through the process of addition (charcoal on paper).³ Such a ‘peering into’ is made even more obvious through the masterful creation of the mulberry paper—fragile, translucent and materially suggestive in a way that demands itself to be seen for what it is. For some pieces, the silhouettes of flora, as in Seen, screen, scatter, seem to be manoeuvring their outlines—but outlines only—all over the surface of the paper. They interact with light, for when light hits, these ghostly traces glow just a little bit more, and when otherwise, they recede into the shadows again, never fully showing their true form. Barred from full access, these other lives seem wholly inscrutable to our human gaze. Other more abstract renditions of the watermark, such as with Paper spine, emits a lure that is texturally tantalising: one is pulled into the fine details, where the undulating terrain may be suggestive of mountain ridges, the human skin, or even just the life of the transformed mulberry itself. We may find ourselves craving to enter this illusive setting, but frustratingly, we can only vaguely peer into it from its surface (funnily enough, sharing a vestige of similarity with the untouchability of the digital watermark). With only partial access to the realm of the within, how can we ever make sense of this mysterious world that refuses to fully show itself?⁴ The translucent traces are at once situations that reveal and conceal, and for better or for worse, we, as designated outsiders, are left pondering and never knowing.

Yanyun Chen, Seen, screen, scatter (detail), 2021, Mulberry charcoal and bark on STPI handmade paper with watermarks, 180 x 55 cm (left); 180 x 55 cm (right)

Within this world of light and lightness, or perhaps shadowy evocations, Chen has rearticulated her familiar motifs in transformed ways. It may be that the unbridled energy of the residency, where the artist and the team were tossing ideas and tests back and forth, had led to her instinctively making decisions that were drawn from her previous practice even as the journey was leading her somewhere else. The appearance of the chrysanthemum and peony, for example, has been a constant since the artist’s days of making observational charcoal drawings among other flower species. The focus on flowers started with a very practical consideration: after returning from her studies in Sweden in 2014, the artist simply did not have the resources to hire live models for her nude drawings.⁵ Moreover, the alternative found in flowers seems to have opened up another vehicle for Chen’s artistic expression—these beings have always been used symbolically in various cultural and literary sources, and are now similarly employed by the artist to touch on sociopolitical matters and existential inquiries.⁶ Flowers have, after all, always been a field ripe in symbolism, such as the chrysanthemum. Depending on where you are at in the world throughout history, these can be a symbol of longevity, joy and vitality, among other auspicious meanings. They are also heavily associated with death and mourning and are thus commonly used as bereavement flowers, particularly the white variety. Having grown up in Singapore, the artist has undoubtedly been touched by the flower’s strong association with death and departures, given the ubiquitousness of its use as a condolence flower across the city’s many florist shops. As for the peony, Chen was inspired by a Chinese legend, where the first Empress of China, Wu Zetian, had ordered for all flowers to bloom in the midst of winter. Deathly afraid of the Empress’ ruthlessness, all flowers in her garden went against their nature to bloom—all except for one, the peony. Enraged, Wu banished the species to Luoyang, a place of harsh weather to keep the peonies from ever flowering. Against all odds, however, they started to flourish. Death and defiance, as encapsulated by Chen’s chosen motifs, reflect two sides of the same coin in the artist’s thinking through of “departures”.

Yanyun Chen, The necessity for departures, 2021, Hardground etching, offset lithography, charcoal and and chalk on STPI handmade mulberry paper, 76 x 53.5 cm, Variation 1 and 4 of 6

This sentiment finds another articulation in series that are organised as variations. Indeed, it is the rhythm and structure which “variations” possess in the domain of printmaking that allows for a lyrical and technical elucidation of “departures”. Each variation is not dissimilar to one another, yet none are exactly the same; each can therefore be considered a sustained departure from the other, as in The necessity for departures and Branch. Note how the imprinted image remains, but its elements deviate as you peer from detail to detail. Further, the artist notes how “the production process was iterative, with each an answer to a previous question”.⁷ In this scenario, we may see how her each of her STPI work are indeed a variation from one to the other, where, in the short and frenzied span of three weeks, Chen’s unfamiliarity with the world of print and papermaking meant a whole lot of improvisation based on what was placed in front of her. In turn, it was also an act of improvisation for the workshop team as the artist put forth ideas that went against technique conventions. So it is, a new journey for both parties.

Prabhavathi Meppayil

Meppayil at work in STPI’s Creative Workshop, 14 July 2020

Meppayil at work in STPI’s Creative Workshop, 14 July 2020

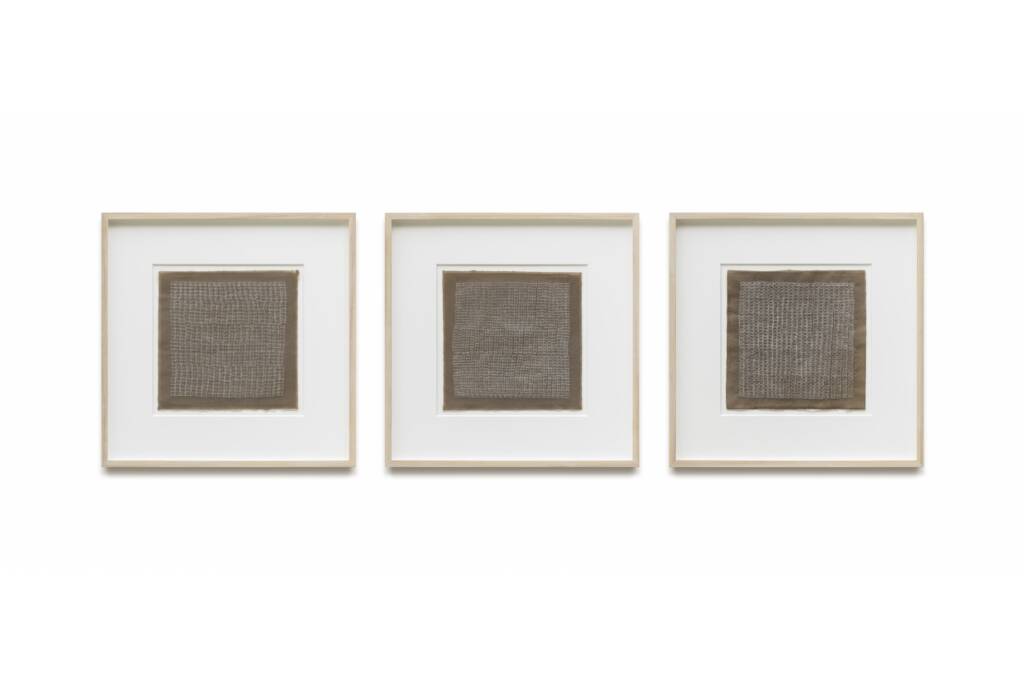

With her three distinct series of works produced at STPI, Bangalore born and based Meppayil brings over her material sensibilities and sensitivities to her collaboration with the workshop. With her t/lp/ series, there is a uniformity in how the geometric, grid-like patterns are embossed into the handmade linen paper. Move closer, and disparate details will emerge: the shape of the grid differs from paper to paper, and the uniformity is disrupted by uneven sequencing. This visual strategy immediately resonates with Meppayil’s pristine gesso canvases—in particular, the variety where she would coat layer upon layer of gesso to build up her canvas, thrusting it into the 3D world before meticulously scratching into the topmost layer using thinnam, a tool used by goldsmiths to incise patterns into metal. Along her other serial works, the canvases/objects have often been read within Minimalist and Post-minimalist frameworks. Additionally, by using thinnam as the mark-making tool and as someone that comes from a family of goldsmiths, the artist has been positioned as a maker who is using the craft from her cultural history.

Top: Prabhavathi Meppayil, t/lp/twenty nineteen ii, 2021, Embossed STPI handmade paper (triptych), 24.5 x 24.5 cm (each)

Top: Prabhavathi Meppayil, t/lp/twenty nineteen ii, 2021, Embossed STPI handmade paper (triptych), 24.5 x 24.5 cm (each)

Bottom: t/lp/twenty nineteen ii detail

In fact, a finer point to be made is how the artist is, in her own words, “critically engaging with the language of the work through the context of [her] lived experience. This is where the histories of artisanal practice, or personal narratives, come into the picture and overlap with the visible geometric vocabulary.”⁸ Vitally important here, indeed, is the threading of her lived experience into the making of her work. Imagine this: the artist in her neighbourhood full of goldsmiths, surrounded by the rhythmic, tapping sound of thinnam against metals. This is the sound that she had grew up with, and this is the tool that she had observed her father using since she was a child. It is with this same tool that she incises into her gesso panels again and again, a bodily rhythm that is not that different from the aforementioned aural rhythms.⁹ The artist is thus informed by her surrounding context from the way that she engages with the language of art itself, one that happens to find confluence with a modernist approach rather than being a derivative. With t/lp/, then, another layer is added: it is not the tool itself that incises into the paper, but rather, its silhouette, or shadow, that is being marked inwards. Having worked mainly with gesso, it must also be an intriguing change for Meppayil to work with paper as the surface instead, a decidedly thinner and more fragile material than the sturdy and thick canvas primer. The image/pattern-making tool journeys from its original use in Bangalore, to a self-reflexive art-making, and finally as just the image itself marked on this foreign material in Singapore, transiting through the space of the workshop.

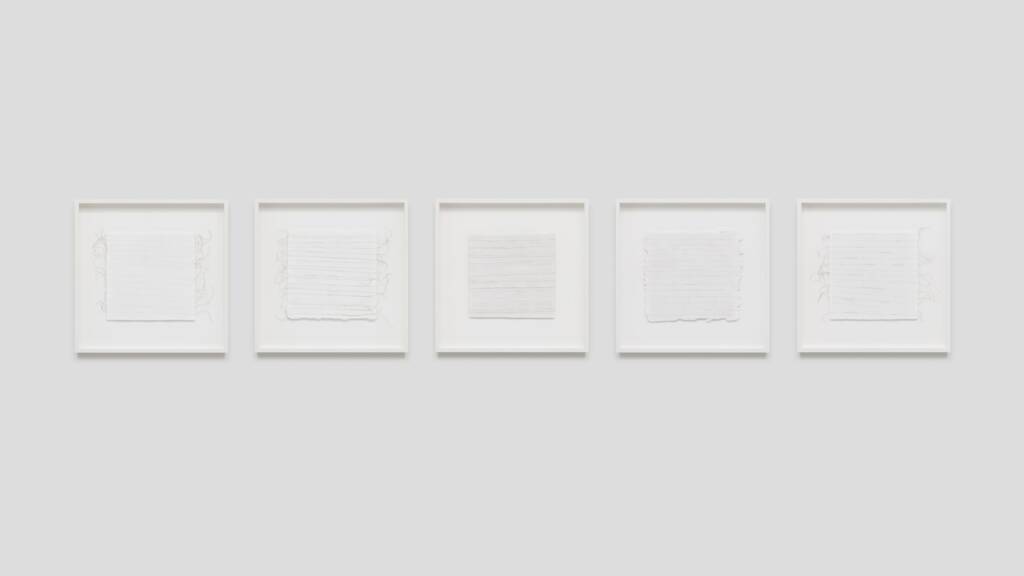

Top: Prabhavathi Meppayil, p/cu/twenty nineteen i, 2021, Copper wire embedded in STPI handmade paper (polyptych), 27 x 40 cm (each)

Top: Prabhavathi Meppayil, p/cu/twenty nineteen i, 2021, Copper wire embedded in STPI handmade paper (polyptych), 27 x 40 cm (each)

Bottom: p/cu/twenty nineteen i detail

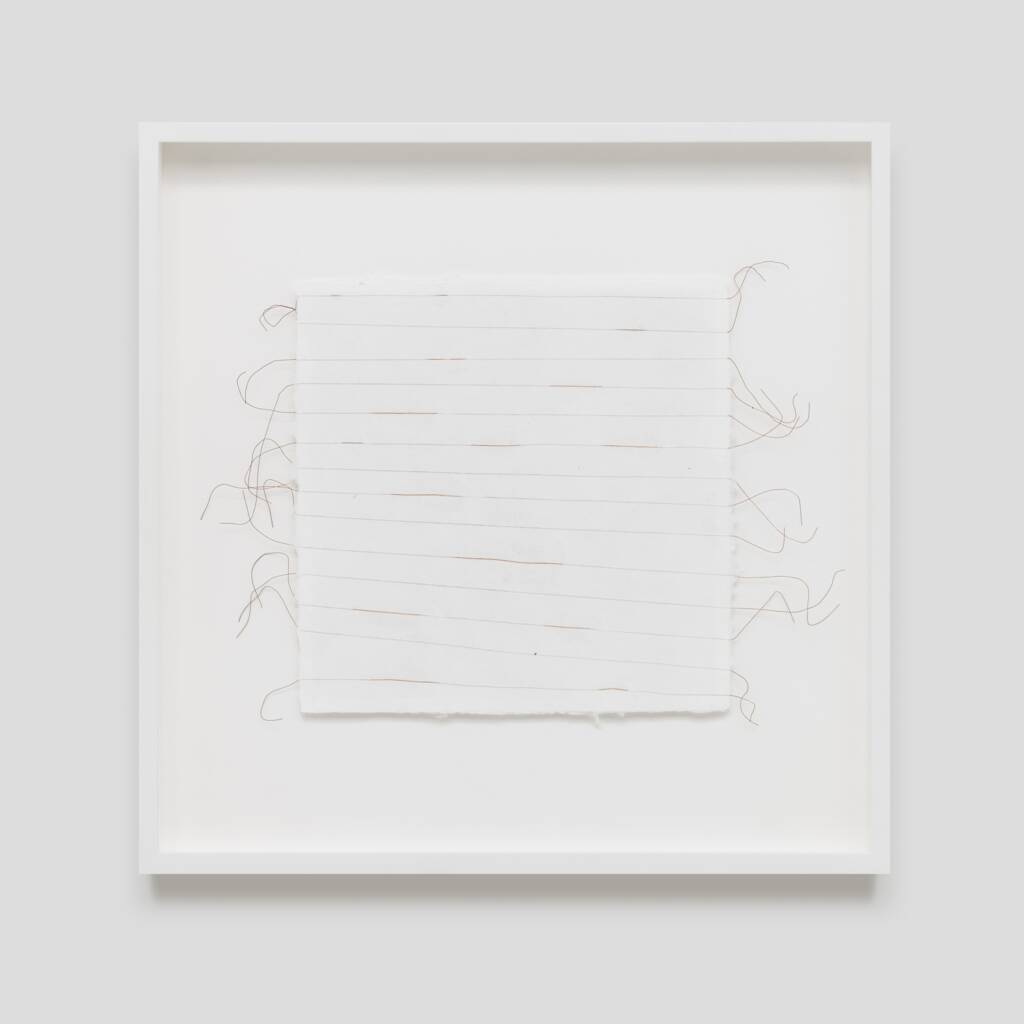

If an element of chance ripples through the thinnam works where the tool dictates the outcome as much as the hand, it is even more pronounced in series that involve the modest copper wire. In her usual practice, copper wires find themselves being embedded in thick layers of gesso as well. Meppayil would then sand at the object, revealing the multicoloured shimmering of the oxidising material. To the artist, rather than try to tamper and control the line to precision, she prefers to let the line speak for itself, their context, their history.¹⁰ Artist Paul Klee ever once said, “The line is a dot that went for a walk,” which underscores the dynamism, expressiveness and movement that a line can evoke.¹¹ Here, Meppayil takes it one step further as she forgoes the control of the dots’ sequencing, but rather, allows the line to determine the course of its own route: “In their own way, the copper wires unravel through the layers of sanded gesso; I cannot control it. Materials have a life of their own, and the element of serendipity makes the materials compelling to engage with.”¹² We see this, for example in the minutest way that the copper lines warp slightly, here and there, despite how orderly it had looked at first glance. Further, Meppayil does not strive to control the environment that the copper exists within, and lets it interact with time and environment itself as visualised through the process of oxidation. However the wire turns out is out of the artist’s hands.

The thickness and opacity of the copper-embedded gesso is swapped with the delicate translucency of the handmade paper used for p/cu/. The process differs as well: rather than inlaying the copper after the gesso layers have been formed, here, it is the copper wires that are being positioned first, before layers of wet paper pulp are poured over it. There seems to be an additional temporal element here where, as the wet paper pulp dries, it coats itself around the copper wire, wrapping itself around it while simultaneously being warped by the excursion of a foreign matter in the fibrous substance, an inter-action between both materials. In its final presentation, we are beckoned to be near these humble-sized works, allowing for the richly patterned copper arrangements to appear before our eyes with each step closer. This is the advantage of the translucent paper: we are permitted to see through and into the layers, allowing the copper lines to reveal themselves fully even as the pulp had formed more thickly in some areas than others. Further, paper here is uneven, rough and wrinkled, and with the deckle edge of most pieces being left untrimmed, therein a chaotic contrast to the geometric and smooth body of her gesso canvases. Perhaps this is another aspect of letting the material speak for itself.

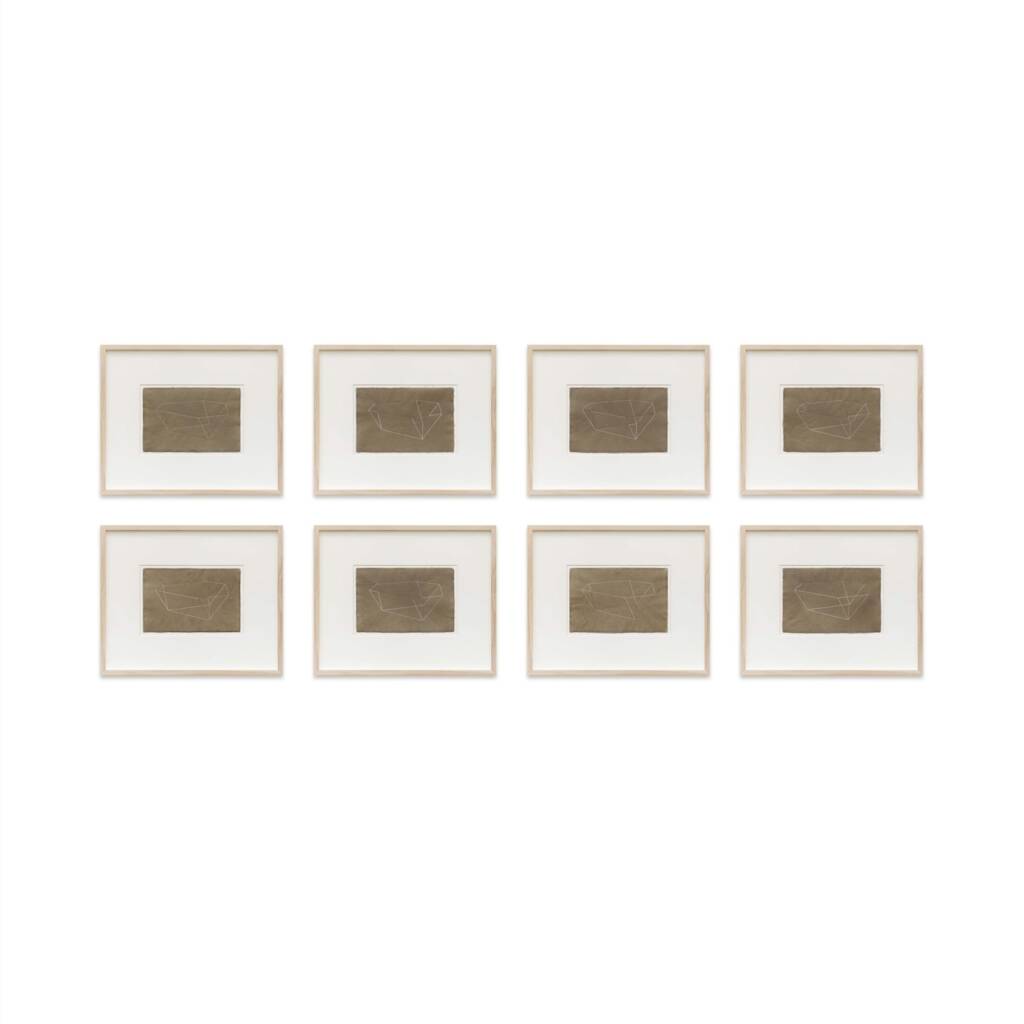

Top: Prabhavathi Meppayil, cu/lp/seventeen, 2021, Copper wire on embossed STPI handmade paper (polyptych), 15 x 23 cm (each)

Bottom: cu/lp/seventeen detail

Finally, the geometric shapes from tools and moulds, and the agency of the copper line, come together for the cu/lp/ series. From far, there is a uniformity in how the embossed lines trace themselves over the handmade linen paper. But again, Meppayil’s works are one that beseech the viewer to come into closer, more intimate contact with them, so that finer details may reveal themselves within the works’ rhythms. As you move from one to the other for each series of eight, you will notice how the copper lines trace different paths across the repeating forms, as if highlighting a different way to interact with the shape each time, almost as if you are repeating time, or maybe space, again. The shapes themselves are artificially enlarged from their original size in their intended use, suggestive of a different scale of being. A few different universes, then, as encapsulated by the tracing and re-tracing of copper lines, surface up together on the same plane. Of course, we must remember the precedence of the material: even in its seriality, each copper line shines differently from another, each piece of handmade paper varies from one to the other. The space for chance yawns wide open as the art-making matter lifts itself from the maker’s hands. This is especially significant given the context in which these works are made, where Meppayil is not working from her studio but rather in a totally new environment with many foreign materials and techniques, as well as not just with oneself but in close collaboration with the workshop team at STPI—thus distributing the control of the making even more. Surely, departing from a certain method of production into another that is ripe with new trajectories.

Hong Zhu An

Hong at work in STPI’s Creative Workshop, 26 May 2023

Hong at work in STPI’s Creative Workshop, 26 May 2023

Paper takes centrestage as we move to the monumental paintings by Hong, born and raised in China and currently residing in Singapore for the last three decades. This is, in fact, Hong’s second residency with STPI, with the first having culminated in his solo exhibition at the Gallery, Ascetic Serenity (2012). Coming back into the workshop, one can say that both the artist and STPI have accumulated years’ worth of experiences, knowledge and ideas in between Hong’s two visits. This time, then, Hong must have been acutely aware and prepared (more than the first time, at least) for the paths that he could take as he embarked on this residency. Indeed, while years have passed, the artist is still well-attuned to the possibilities of the workshop; in particular, the paper mill, where he had worked in and with extensively for his first project. So, being an artist with a strong sense of his own unique visual language and explorations, he entered the workshop with a precise vision of the outcome.

Having been raised in the traditions of Chinese brush since four years old by his family, Hong was trained as a wood sculptor at the Shanghai Art & Craft Institute and subsequently in Western Art Painting at the Sichuan Art Academy. Hong later sojourned to Australia from 1989 to 1993 and was exposed to a whole other realm of art, before finally settling down in Singapore since 1993 to present day. Apart from painting, Hong has also dabbled in sculpture, ceramics and pottery, and even working with textiles. Moreover, this range of trainings and experiments has all led back to his faithfulness in Chinese painting, and a lifelong desire to push forward the language of this genre into contemporary times.

Hong Zhu An, 云间片帆 Sail between the clouds, 2022, Cel vinyl paint on paper pulp, on STPI handmade paper (diptych), 132 x 168 cm (left); 132 x 167 cm (right)

Hong Zhu An, 云间片帆 Sail between the clouds, 2022, Cel vinyl paint on paper pulp, on STPI handmade paper (diptych), 132 x 168 cm (left); 132 x 167 cm (right)

A unique aspect of his practice, for example, is his probing use of the Chinese ink. In the realm of Chinese ink brush painting and calligraphy, the stroke is a means to the end to capture the essence of things, be it pictorial scenes or poetic verses. Indeed, these two highly-regarded art forms in Chinese culture share many similarities in terms of artistry and skills, and can often be seen sharing the same surface. For Hong, his brushwork goes one step further by honing in on the energy of the stroke itself through a process of abstraction, thus lifting it away from any direct interreferential associations.¹³ Of course, that is not to say that his paper works are totally devoid of any earthly allusions. In fact, in some rare cases, mild figuration even makes it into his work: a fish, bamboo branches, lotus roots. Rather, what the artist has done is to meld these instances with the frame of references he has accumulated from his own practice as well as his external exchanges and journeys. This is easily perceptible from the other elements that comprise his paintings: an adept use of colours, modern and striking compositions, and a playful manoeuvring of his ink subjects. Viewed altogether, it is not easy to read these as purely (colour field) abstract works, or as faithfully following from his traditional Chinese training even as he consciously draws from this well. Rather, Hong has indeed found a new formula that is undeniably his, allowing for his paintings to be read in and of itself without the burden of being fossilised in history or a particular place-time. Coupled with his evocative titles, each work sets out to move its viewers towards universally-felt emotions and states of being, personal and transcendental. Hong, then, has achieved what he had set out to do, which is to propel his heritage into what we perceive as a globalising 21st century.¹⁴

Hong painting with paper pulp

Hong painting with paper pulp

At STPI, the layers of paint in his usual practice trades itself for layers of pulp, imparting on his paintings a wholly different texture. This was true for both residencies undertaken by the artist, where he was introduced to a new art-making material, that of coloured paper pulp. Working in the cold and damp conditions of the paper mill, Hong trades his brush for his own two hands to work with the wet fibres, extending the use of paper as mere surface to almost-sculptural material, moulding his colours and compositions into a highly textural finish. Rather than washing layers of ink and paint to create his depth-filled planar backgrounds, paper becomes the main actor in manifesting the art object, conferring upon the final works a subtle sturdiness that metaphorically and literally jumps out beyond the two-dimensional surface in contrast to his more translucent studio works. Indeed, many residency artists who have passed through STPI’s doors have been struck by the potential of paper as palette, sculpting material, or even a mechanism for which other raw materials can enter and be transformed. Paper, malleable in such ways, lends an intrigue to artists who have encountered it as such. Hong’s willing return to STPI can be a testament to that.

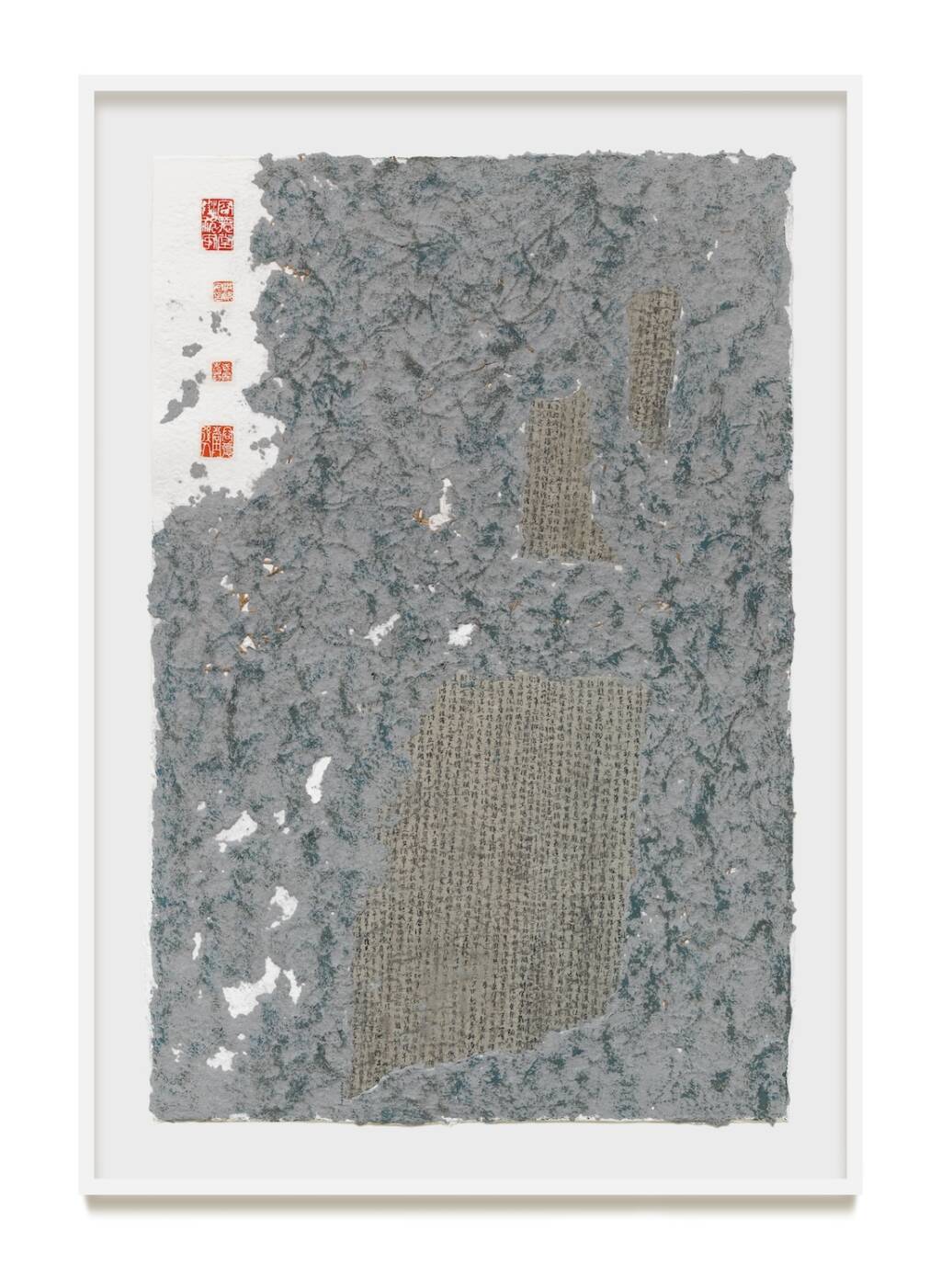

Hong Zhu An, 水月 Water Moon, 2022, Coloured paper pulp with calligraphy embeddings on STPI handmade paper, 120 x 80 cm

Hong Zhu An, 水月 Water Moon, 2022, Coloured paper pulp with calligraphy embeddings on STPI handmade paper, 120 x 80 cm

In any case, the artist’s steadfastness to Chinese ink still stands. In works like 想思处 Thinking Place and 水月 Water Moon, for instance, there is an almost archaeological feel to how certain expanse of the work’s ‘facade’ seems to have peeled off, revealing another layer beneath. Underneath, we can make out some steady lines of calligraphic verses, rhythmic and boundless. It would be useless to try to make out the meaning of these verses, whether you are a native speaker or not; Hong has made it deliberately so as this is not the main point. Rather, the emphasis is on an appreciation of the structure and encounter of the form—at once, an aesthetic¹⁵experience. Whereas in works such as 初夏 Early Summer and 云间片帆 Sail between the clouds, the stroke is liberated from its conventional formal use. Instead, they appear as masterful lines, splotches, wind currents, waves and rivulets across the coloured paper pulp bodies, engaging in an energetic chorography that seems almost too substantial for the frame that it resides within. By making these strokes interact with abstractions from nature (both from the titling and from the image itself), Hong at once deepens our reverence for the ineffable depths of ink, while evoking a rousing connection to the world around us from inner landscape to outer landscape; the latter, of course, bearing a similar philosophy as the traditional Chinese “shan shui” (quite literally, “mountain-water”) paintings. Even at close to 70 years of age, the artist’s relentlessness in pursuing his source of truth through his practice is admirable, as is discernible from the easy translation in meaning and aesthetic between his studio and STPI works. “A lifetime of toil for a singular goal, one cannot give up halfway, or be in two minds about it, or agree today and lie tomorrow, no, it is a lifetime of work and one has to be stubborn about it. Painting is the ultimate goal.”¹⁶ And so, his diligent journey continues.

Hong Zhu An, 初夏 Early Summer, 2022, Cel vinyl paint on paper pulp, on STPI handmade paper (diptych), 119 x 80 cm (left), 119.5 x 80 cm (right)

Hong Zhu An, 初夏 Early Summer, 2022, Cel vinyl paint on paper pulp, on STPI handmade paper (diptych), 119 x 80 cm (left), 119.5 x 80 cm (right)

To conclude,

So it is that departing can call to mind a journey of sorts. And in journeys, one is always in the process of moving from one to another; a fitting way to think about how artistic practices are one of explorations. After all, practice means always doing, renewing and continually building on what has already been done. Coming to STPI, another path has been introduced to the practices of these artists, and to be sure, the practices of all artists who have experienced a residency with this institution.

And what of STPI’s own practice? The workshop itself is not a static space. The ardent team members that compose it are on their own expeditions as well, with every project impressing upon them the trace of what has happened. Each residency offers that fertile space for the workshop to engage in their own experimentations, as they welcome and realise the possibilities and challenges that the artists pose to them. Each relationship leaves their residue in the space of the making and in the lives of the makers, brought forward each time in tangible and intangible ways. So it is that departing is from one journey to the next, onwards each time.

Footnotes: